ResearchED Surrey was a superb event last weekend, and I felt very lucky to be able to present a talk in such distinguished company. My talk was entitled ‘Breaking (then making) productive classroom habits’. It was based on this paper, published with Sam Sims and Rebecca Allen, about how habitual behaviour could be limiting teacher effectiveness (an open access version of the paper is available for download here). Rather than review the study itself in too much detail (as this has already been done elsewhere e.g. here, and the research paper can be read if you would like to), I thought that I would try to just summarise a few of the key ideas that I wanted to stress. The slides are also available here.

Teachers ‘asymptote’ in effectiveness, and CPD doesn’t work

Matthew Kraft and colleagues have shown that if we plot ratings of teacher effectiveness against years of experience, as in the example below, we see a funny pattern emerge where teacher effectiveness increases rapidly in the first few years of their career, before levelling off (mathematicians describe this as an ‘asymptote’). Teaching is sometimes described as a ‘sink or swim’ profession, and we can see clearly that in order to swim, new teachers have to make very rapid progress. The problem is that after this period, for each subsequent year of experience that we have, we see to make less and less impact on the progress of our students.

In addition, interventions designed to improve educational outcomes very often don’t work, despite our best efforts and billions of dollars/pounds of taxpayers’ money. Commonly these programs target teachers (for example aiming to increase their knowledge, motivation or skills), making the understandable assumption that this would be likely to improve student outcomes. But this is very often not the case. The vast majority of educational interventions focused on teachers fail to translate into improved student outcomes.

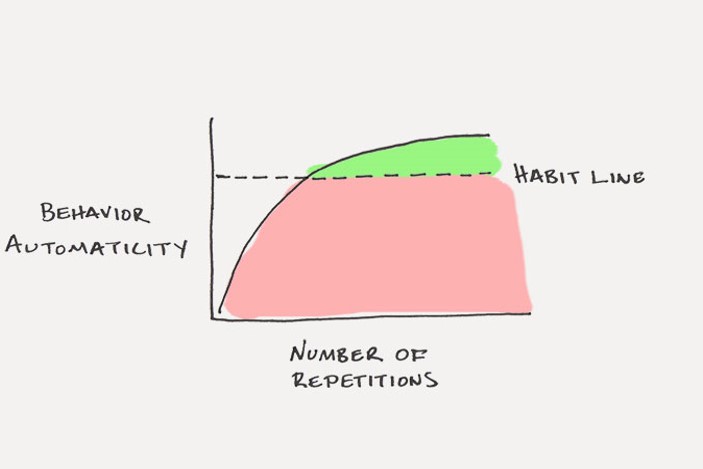

So teachers asymptote, and efforts to reverse this rarely succeed. Why? Well one possible reason is habits. Indeed the asymptote in teaching effectiveness above looks strikingly similar to the sorts of graph that we see in studies of skill learning when behaviour switches from being ‘goal-directed’ to being ‘habitual’.

Habits are a completely separate kind of behaviour to normal ‘goal-directed’ behaviour

As defined in the academic literature, habits have four key features. They are:

- Ordered, structured action sequences

- Automatically elicited by environmental cues

- Insensitive to goals or rewards

- Associated with separate anatomical circuits

It’s important to emphasise the implications of these. Habits are therefore behaviours which we produce automatically, in response to an environmental cue, and without any consideration of the consequence of the action. They are reflex reactions to a particular context. This helps us to see how habits can easily become unproductive, as we might continue to automatically produce them long after the benefits of the action have disappeared. The fourth point, for me at least, really rams this home as it emphasises a how when a behaviour shifts from goal-directed to habitual, it moves to an entirely different brain circuit which operates according to entirely different rules. Habits are qualitatively, rather than quantitively, different behaviours.

Put all this together and we can see why habits are so hard to shift. Habits don’t operate on a spectrum where just a bit more willpower or a bit more knowledge will help us to overcome them. This helps us to explain why so much CPD (which will often target teacher knowledge or motivation) fails, as changes in goals will have no effect on the automatic production of an established habitual behaviour!

There is both indirect and direct evidence for habitual behaviour in teachers

There are two main reasons to suspect that habitual behaviours are prevalent in teaching

- We have both direct (e.g. from teacher reports) and indirect (e.g. from observations) evidence that teachers display the features of habitual behaviour (such as automaticity and outcome insensitivity) in the classroom, and that this increases with years of experience.

- Teachers work in environments which have many of the features known to both accelerate the learning and facilitate the production of habitual behaviours, for example stress, time and performance pressure, and frequent responding.

More detail on the studies reviewed to come to these conclusions, in addition to our own research using TeacherTapp, can be read in the paper.

Asymptote as ‘locked-in survival habits’?

One very plausible explanation for the asymptote in teacher effectiveness, therefore, is that during the initial years we are developing ‘survival habits’, behaviours which allow us to swim rather than sink in the overwhelming and confusing place that is the school classroom. In that these habits might be things that allow us to remain in the profession, they serve a crucial and valuable function. BUT… once formed, they can all too easily become locked into our practice, especially given an environment that is highly conducive to forcing us to fall back on habitual behaviour. As our reactions in the classroom become more automatic, so our ability to consciously shift these (e.g. due to changes in our goals or knowledge, or changes in the outcome the behaviour brings) will be reduced.

Let’s look at some examples:

I put out an appeal on Twitter, complete with an example of one of my own unproductive habits

I got some very interesting responses, but two rough categories were by far the most common:

- Inefficient mechanisms for checking for understanding

- Talking when students are silent, or otherwise accidentally disrupting them just when they are doing the thing that you actually want them to do!

I think it’s easy to see how both of these behaviours could form early on as survival habits. New teachers need to establish themselves as an authority in the classroom. One simple way to do this early on is to make sure that you remind students of your presence frequently. Filling silences with praise, interesting asides, observations on common errors in the work, reminders of the amount of time left etc etc is one way to make sure that you remain present in students’ minds. From the perspective of helping to control behaviour, this could be a very useful survival habit. After a few years, however, when the teacher might be more confident in their ability to let a class work independently for a greater length of time, it becomes less productive, or indeed downright harmful to the aims of the class.

Inefficient checks for understanding, such as asking “any questions?”, or “all ok?”, as well as being just so natural, could arise easily in trainees out of a genuine desire to ascertain levels of understanding, but who haven’t been shown more effective methods. They also show students that you care about their learning (even if none of them ever say anything), and help again to establish a presence as an authority in the room. It doesn’t take long for habits to form in the right environment and with frequent repetition, so even a few months of this before being introduced to more effective methods might be enough to lock in a subsequently unproductive behaviour pattern.

Breaking classroom habits

Breaking (and replacing) unproductive habits requires, as we have said, more than just willpower alone. It can be achieved in the same way that the original habits were established: through repetition of the desired behaviour in the presence of the relevant environmental cues. So what does that mean for teaching? It means repeatedly using of a new technique or approach in a realistic (or near-realistic) classroom environment.

One type of professional development which incorporates aspects of deliberate (and intensive) practice of new skills is instructional coaching. There are numerous types of coaching out there (for example Josh Goodrich gave a great talk at ResearchEd Surrey on ‘responsive coaching’ and I’d recommend his blogs on the subject), but a stereotypical coaching cycle might involve rehearsing new techniques in a controlled environment, then implementing them in a real lesson (often captured on video), then receiving feedback from an observer, re-practising, and then re-implementing the technique in a subsequent lesson.

Instructional coaching is one of the most strongly supported forms of CPD in terms of its ability to bring about changes in teaching practice and improvements in pupil test scores. In the paper we argue that this is at least partially because it seems to be better suited to breaking habitual behaviour associations than more traditional ‘information delivery’ models of CPD.

Coaching… in a non-coaching school

Whilst it would be great for all of us to be in an environment where coaching was the norm for CPD, for many reasons that is not (yet?) the case. I’m not. My school is actually quite a long way from being ready for the sort of centralised CPD system that coaching represents. So what can those of us who work in these sorts of environments do to break our locked-in survival habits? Well I would argue that a lot of the useful ‘active ingredients’ of the coaching model (such as the five features in the picture above) can be adapted for small group collaboration. For example, you can aim to make your own CPD targets and practice:

- Individualised – working with a trusted partner, with both committed to improving the other’s practice as well as their own

- Intensive – meeting/interacting/observing at least every couple of weeks

- Sustained – not moving on until you are SURE that the new behaviour is established as a productive replacement habit. As a rule of thumb: no new CPD aims should be allowed until the first new behaviour has survived at least one decent school holiday!

- Context-specific – teacher expertise is highly context specific. I can feel like an amazing teacher with one class, and an awful one with the next. CPD should be targeted extremely specifically, such as ‘implementing think, pair, share, successfully with 9c’. Laser focus on our own particular areas for development may mean that we feel like we are making very small steps forward (there will always be a million things that we would ideally like to improve), but at least it’s likely to mean that we are moving forward in the first place.

- Focused – using deliberate practice of the targeted behaviour in a realistic environment (though often away from the stresses of a real lesson initially)

In this way, hopefully we all have a decent chance of ‘beating the asymptote’ and ensuring that the automatic routines that we build as teachers are ones that will allow continued improvement for us and our students; not, in the words of Dylan William, “because we are not good enough, but because we can be even better.”

Really enjoyed this look at the research, thank you. I think your conclusion about how to break the habit is less likely to succeed. It is akin to learning to eat healthily or exercise with intensity by focusing on only one day per week. You need to go all in, every class, every day – even when the habit is wrong for that class – so that over 4-6 weeks you can then pull back and work out where it is necessary 100% of the time, and where it might be more flexible.

LikeLike

Interesting idea. Thanks for your thoughts. I think that the ‘overtraining’ of a skill can certainly be a possible tool. Give how context specific some of the behaviours we might be trying to implement, though, it might be something that is far from ideal in some other places

LikeLike

[…] started thinking more about these habits when listening to Mike Hobbiss at researcED Surrey, he mentioned a question he’d asked on Twitter about which habits teachers find it hard to break, […]

LikeLike

[…] all have habits as teachers, some good some bad. Once acquired they can be hard to shift; when we stop really having to think about them then we move from conscious to unconscious […]

LikeLike

[…] are deeply embedded and schools are not conducive environments to changing them, as Mike Hobbis has explained very persuasively. If we want teachers to act on feedback, we need to get serious about devoting time and resources […]

LikeLike

I am very glad I found your blog, so many interesting topics. Thank you for sharing this one too.

Just taking a step back, I wondered what do you think is the value of breaking above the habit line? What’s the value of those incremental increases on the learners if say, they are already achieving? Is it so tiny that there wouldn’t be a proportional effect on the learners? Or would it have a higher impact on dis-advantaged / or higher-performing learners more?

This is only a tiny thought btw. and I’d love to hear your thoughts. If teachers are just “surviving”, would there be a more valuable use for their effort that instead of coaching to break the habit line, to say maybe have longer breaks, a meditation room or a boxing room 🙂 ? Would that have an impact on the survival, the wellness and also the habits?

Thanks again for sharing, I’m now going to go find your post on, “Constructivism is a theory of learning, not a theory of pedagogy. Neuroscience explains why this is important” as that’s what brought me here!

Best, dpc

LikeLike

Hi Dan. Thanks for reading and I’m glad you have enjoyed the posts! I’m certainly in favour of a slower introduction to teaching for early career teachers – lighter timetables and more deliberate practice (and maybe boxing rooms as well!). That would presumably slow the initial formation of ‘survival habits’ (and hopefully reduce the stress and teacher turnover associated with the first 5 years of the job). In England, the new ECT seems to aim to do this… although anecdotally I’m not sure it’s really succeeding.

That said, I think that it’s always likely that some habits which have previously been useful turn out not to be any more. In which case, we’ll probably always need a mechanism for trying to shift unproductive habits to more productive ones.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh interesting, so slow the approach early to stop those habits forming early – that’s a good thought.

All the best, dpc

LikeLike

[…] Old habits die hard – my ResearchED Surrey 2021 presentation […]

LikeLike